Darwinism's Generations

Martin Hewitt's generational history

Generations before Generations

Long ago, in the mists of prehistory, generations had no names. Fifteen-year cohorts were born, aged, and died, without anyone thinking to call them “Lost” “Boomer,” “Millennial,” or even to designate them with a single letter. For the generationally inclined, there are two ways to think about this undifferentiated expanse of human time. Option one, which we might call the Mannheim Option, is to declare that there were no social generations prior to the nineteenth or twentieth century—that they’re a modern phenomenon, arising with the French Revolution and the birth of history. Option two, which we might call the Ortega Option, is to argue exactly the opposite—that generations not only preexisted their discovery, like oxygen or Antarctica, but actually formed the hidden pulse of history.1

Most scholars who study periods before the twentieth century don’t use generational analysis. Implicitly, they’ve taken the Mannheim Option. But as I’ve argued here before, that’s a mistake: generations are a powerful and underused way of thinking about the experience of history in the past as well as the present. Over Thanksgiving break, I had the chance to make that case in a workshop for graduate students on “generational thinking,” together with the brilliant Victorianist Martin Hewitt.

Martin and I argued that you don’t have to wait for generational nomenclature to see generations in action. Generations “in themselves” precede generations “for themselves,” as Martin put it, alluding to Marx’s distinction between “class in itself,” the structural position of a class, and “class for itself,” class consciousness. (Martin began his career as a labor historian.)

Darwinism’s Generations

While my argument for premodern generations rested merely on my own intuitions, Martin had hard proof on his side. His recent book, The Reception of Darwinian Evolution in Britain, 1859-1909: Darwinism’s Generations (2024), studies the reception of Darwinian evolution across more than 2,000 nineteenth-century men and women, segmented by generational cohort. The questions this extraordinarily ambitious book poses are fundamental: was Darwin right to argue that his theory would ultimately triumph not because it persuaded the establishment, but because it appealed to “young and rising naturalists”?2 Is generational replacement, as Thomas Kuhn argued, the essential motor for paradigm shifts?

The answer to both questions turns out to be a resounding “yes.” In 1859, when The Origin of Species was published, Darwinism’s triumph hardly seemed inevitable. The reaction in the press and among the public was virulently hostile. The deepest religious principles seemed to be under threat; attacking Darwinism was an instinct and a duty. To early observers, the fate of this deeply unpopular theory must have seemed tenuous at best. But if contemporaries had analyzed the reaction along generational lines, they would have realized that Darwinism’s prospects were far better than they initially appeared.

The oldest members of the public, those born in the eighteenth century, were Darwinism’s most implacable enemies. In general, they didn’t bother to argue with Darwin, confining themselves to expressions of incredulity or disgust. The Origin of Species was “wonderful to me, as indicating the capricious stupidity of mankind,” Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) remarked. He “never could read a page of it, or waste the least thought upon it.” His wife Jane Carlyle, though born a little later (1801-1666), agreed: the idea that humanity was descended from “the great original Oyster” would have been offensive, if it weren’t so ridiculous. The only possible reactions were laughter or silence.

Most members of Darwin’s own generation, born in the first decade and a half of the century and already in their late forties or fifties when Origin appeared, were equally antagonistic, but their response was different. Rather than ignoring Darwin’s theories, they tried to argue against them. They found errors of reasoning or failures of evidence; they pounced on each inferential leap, each gap in the fossil record. “His mind is of the German type,” the Whig politician George Cornwall Lewis (1806-63) complained, “speculative, laborious, and unsound.”

Move down one generation, and the response shifts again. Among the men and women born between 1814-29, those who would have been in their thirties to early forties, few accepted Darwin’s ideas to the letter, at least at first. Instead, they searched for tentative compromises. “Without being a Darwinite to the entire length he goes,” the anatomist George Rolleston (1829-81) wrote, “I cannot avoid being one as far as man goes.” They argued with Darwin; sometimes they even attacked him. But they were willing to use bits and pieces of his theory, even if they could not accept it wholesale.

But exactly as Darwin predicted, it was among those who were teenagers or still in their twenties when Origin appeared that his ideas caught fire. Their immediate response is far more difficult to trace, since (then unlike now) few teenagers had the opportunity to publish their thoughts; as a result, it has remained largely hidden from view. But this is where Hewitt’s superb archival detective work comes into play. In letters, journals, and reminiscences, he shows how Darwin made immediate converts among the youth. The theory of natural selection percolated among university students like the future astronomer Sir Robert Ball (1840–1913), in his own words an “instantaneous convert,” who read Origin with “intense delight.” When the young Samuel Butler (1835-1902) encountered Origin while working on a sheep farm in rural New Zealand, the whole course of his life was changed.

It was these young men and women who would shape the reception of Darwinism in the years to come. As Darwin continued to publish his theories, with The Descent of Man appearing in 1871, he converted some of his antagonists. But many more simply died or left the intellectual scene. Meanwhile, the precocious teenagers who devoured Origin at school or university became the next generation of scientists, novelists, intellectuals, clerics, or simply members of the public, doing their small part to shape the course of public sentiment. In time, they too would cede to younger generations, for whom Darwin would become merely part of their heritage, not an intellectual cataclysm.

Hewitt’s story of the slow acceptance of Darwinism shows that generational replacement really is a mechanism of intellectual change. But he also reveals a different, and stranger, truth about history. The young ultimately succeed the old, but in the meantime, multiple generations have to coexist: together, working from different vantage points, men and women at all stages of the life course shape history. It is this intricacy that gives intellectual life so much of its interest. As Hewitt writes, “just as the German ‘geschichte’ (history) has etymological roots in ‘schichte,’ that is layer or strata, so the social, cultural, and intellectual history of past societies can better be understood as a layered rather than unitary phenomenon.” His own richly layered story of the triumph of Darwinianism is now one of the fullest accounts we have of intellectual history in human time.

Periodical Culture

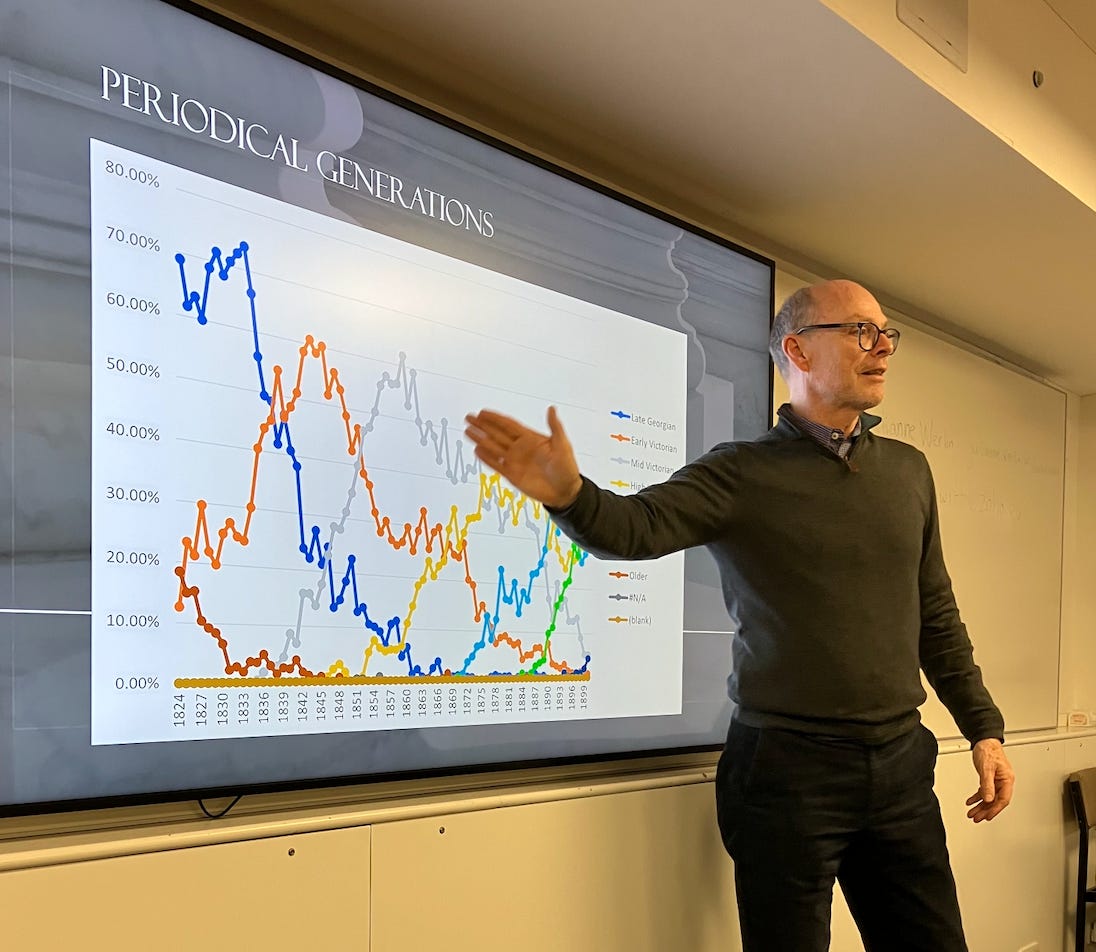

In order to study Darwinism’s generations, Hewitt had to define date ranges for each cohort. There are no established generational cohorts in the Victorian era, so that meant creating his own demarcations. If social time flowed perfectly evenly, any division would be as good as another. But we all know it doesn’t: history has its eddies and rapids, moments of comparative stasis and quick acceleration. Hewitt had to find the natural fissures that best matched intellectual history. He did this, ingeniously, through mapping the rise and fall of contributors to Victorian magazines and newspapers using the Wellesley Index to Victorian Periodicals.

Hewitt with his stunning graph, reproduced here with his permission

The best generational divisions are the ones that lead to the clearest demarcations of cohorts in the history of publication. Move the divisions five years backward or forward, and the peaks become lower, the cohorts less sharply defined than they are within Martin’s scheme. (You can also see something else happening in this chart, which I asked Martin about at the time: the career length of writers lengthens over the course of the century.)

In using periodicals to derive his cohort ranges, Martin implicitly gestures toward another aspect of generational history: the rise of generational consciousness through media culture. Although I began this post by arguing against the equation of generations with generational consciousness, generational consciousness is important in its own right. Periodicals play a special role forming it. Far more than novels, poems, plays, or even essay collections, they’re predicated on a literary culture governed by regular cycles of change. As a result, they both reflect and create a shared generational sense. So long as periodicals continue their ineluctable march onward, and authors cycle in and out of them, literature has a clear progression and flow.

Like many on Substack, I’ve found myself thinking about periodical culture recently and its implications for literature and scholarship.3 Unlike philosophy or the social sciences, literary studies is a book field, not an article field—an artifact of our own preferences, perhaps, but one that has been rigidly reinforced by requirements for tenure and promotion. Were we wise to adopt this as our standard? By marginalizing journals, we’ve sidelined the major vehicle for intellectual conversation, the medium that was capable of giving the field a sense of coherence and forward momentum. Books move the field forward too, but they’re much more self-contained; ideally, they’re also more permanent and less topical. Now, with the internet’s effective dissolution of journals, replaced by the mechanism of “search,” there’s another level of flattening. Have we damaged our capacity for intellectual progress by letting our periodicals recede into irrelevance?

Possibly. And yet! Recently a gleam of hope has emerged on the horizon. Substack readers will realize that I refer to Literary Imagination and to Paul Franz’s editorial work to make the journal one that people read as a journal, with each issue constituting an event. Perhaps there’s still the potential to create a continuous conversation, if only we’re able to grasp it.

Or if not us, then the next generation.

Karl Mannheim’s classic essay on generations still defines the parameters of debate: it’s hard to think of another century-old essay that exercises so great a dominance in contemporary discussions of a social phenomenon. But the work of José Ortega y Gasset opens up another, approach, one that is under explored by comparison.

This quotation, and those below, come from Martin’s book.

I’m thinking of conversations on Substack about short fiction and periodicals, catalyzed by Naomi Kanakia’s superb writing on short stories and American magazines and continued by Andras Kisery, Alan Horn and others. The work of Sam Kahn in founding multiple Substack magazines has also played a role; the appearance of the New Yorker on Substack probably hasn’t hurt either.

So great, as always.

As my mind is of the German type, “speculative, laborious, and unsound," it occurs to me that the phenomenon Hewitt describes in relation to Darwin is also visible in the reception (within Germany) of Kant's philosophy. The younger German Idealists had read Kant and Fichte as teenagers, and they were extremely conscious of the difference between themselves and writers who came to Kant and Fichte's theories in middle age or later. (Ironically, this latter group included Kant and Fichte themselves. The elderly Kant publicly denounced his idealist disciples, writing "May God protect us from our friends. Our enemies we can take care of ourselves." And Fichte eventually had the same problem.) Goethe, who at least in the 1790s and 1800s was the member of the older generation most eager to keep up with the philosophical cutting edge, kept hiring ever younger professors at Jena to help him keep abreast of what was going on. (Schiller, Reinhold, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel as a postdoc: the talent pool was deep!)

When Hegel got his first regular professorship and Heidelberg, he made a big effort to reconcile with Fritz Jacobi. He'd come to the conclusion that Jacobi's religious critique of Fichte had been useful in helping to move modern philosophy forward, and that his differences with Jacobi were generational. Upon Jacobi's death he makes some remark in a letter that I can't recall precisely, I want to say that a whole generation had passed away or that Jacobi was the last of a heroic generation or something (ironically, as the shape-shifting Goethe would live for more than a decade). But I bet I'm modernizing the phrase, I'll look it up when I get a chance.