A Disreputable Book

In 2018, the American Historical Review, the flagship journal of the American Historical Association, published the eleventh entry in its annual series of conversations, a written discussion between a small group of historians on a theme of general interest.1 Previous topics had included the question of scale, transnational history, and the history of emotions; the subject selected by the editor for 2018 was “generations.”

The conversation was a brilliant one. The eight participants, scholars of twentieth-century Africa and China, of nineteenth-century American and Reformation-era Europe, ranged widely over the different aspects of the problem of generations, alluding to the fraught intersection between national politics and subjective experience, the family as a scene of comfort and conflict, the shifting sands of memory, and much else. The more theoretically inclined invoked the classic cadre of generational theorists—François Mentré, Karl Mannheim, José Ortega y Gasset, Margaret Mead, and Pierre Bourdieu—alongside their fellow historians.

But there was one pair of names that didn’t appear in the conversation’s 43 densely footnoted pages: the pop historians and policy consultants Neil Strauss and William Howe. The omission of the two was, to say the least, predictable. No academic historian would be likely to refer to them, except in the form of vicious satire—Lawrence Stone, perhaps, in a particularly frolicsome mood. Yet no English-language writers have done so much to shape the discourse on generations.

Strauss and Howe are best known for Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584-2069 (1991), their first collaboration, which proposed an interpretation of American history, and by extension all history, organized around a predictable rhythm of generational change. In the 1990s, the book was not only a bestseller, but helped to set terms of discussion. Its success led them to write a small library of other books on the same theme, including 13th Gen: Abort, Retry, Ignore, Fail? (1993) and Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation (2000)—they’re responsible for that generation’s name. They also started a consulting business: LifeCourse Associates. As that enterprise makes clear, the two aren’t historians or social scientists, but political consultants; their work came out of, and had its biggest impact within, that fluid and febrile world. Al Gore, famously, gave copies of Generations to every member of congress. Steve Bannon is an obsessive admirer, whose documentary Generation Zero is apparently based on the book. Countless newspaper pundits have mined their ideas for columns.

I love grand theories of history, especially if they’re liberally sprinkled with tables and graphs, but Strauss and Howe’s work falls pretty far outside the usual parameters of my reading. Still, as I’ve mentioned before, I’m currently in the early stages of thinking about a generational history of literary authors. I’m more sympathetic than most to the idea that generations might be, if not exactly the key to all mythologies, at least one digit in that vast, combinatorial code. Besides, the ideas of a book like this already are in the air; if they can’t be salvaged, they have to be argued against and dispelled. So I checked Generations out of the library.

Two Books in One

It will probably surprise no one to learn that Generations is not a good book. But it’s easy to see why it was successful. It has the fatal charm of an interesting intuition taken in a truly unhinged direction. For a theory of this kind to be seductive, plausible observations need to be yoked to lunatic impulses: it’s the most bizarre elements, after all, that let readers feel they’re seeing behind the veil.

First the plausible. Generations begins from the premise that people’s position in the life course at any given moment shapes their response to history. Children, young adults, the middle aged, and the elderly will experience a revolution or a stock market crash differently; conversely, what it means to be a child or young adult or middle aged or elderly will be very different in different historical moments. That same revolution may change the nature of childhood all at once by bringing women into the workforce; that stock market crash may make it impossible for the middle aged to retire once they reach their next life phase. “We treat generations as people moving through time,” Strauss and Howe remark, “each group or generation of people possessing a distinctive sense of self” (32). The only way to really understand how men and women confront history is by tracing the whole trajectory of their lives.

It goes without saying that this isn’t an original idea, but Strauss and Howe are right to suggest that the full range of insights it enables haven’t been incorporated into mainstream history, much less into literary history. It’s fascinating to think about how childhood conditions shape the later careers of intellectuals and artists, politicians and ordinary citizens. Outside of occasional biographies, you won’t often find reflections on how styles of parenting thirty or fifty years prior shaped the work of mature writers and artists. And for periods prior to the twentieth century, scholars of literary or intellectual history rarely think very carefully about the impact of demographic structures.

Did you know, for instance, that in the 1870s—the decade when Theodore Dreiser and Willa Cather, Gertrude Stein and Robert Frost were born—Gentle Measures in the Management of the Young was the leading parenting manual, advocating a new, softer style of childrearing? We can, perhaps, hear an ironic echo of the platitudes of that era in the poetry of Frost, just as Blake echoes and ironizes the children’s hymns of Isaac Watts. Or that by 1910, in their early teens, the children of the Lost Generation had entered the labor market at a greater rate than any generation before or since—their childhood lost even before the outbreak of war?

Information like this is scattered throughout the book, alongside timelines, statistics, and tables. Even without any especially penetrating analysis, a cleverly arranged sequence of facts is always suggestive. And Strauss and Howe certainly have facts—many of them of the most intriguing kind. If they had been content to explore this dimension of history, Generations might have been a fine book.

Cycles of History

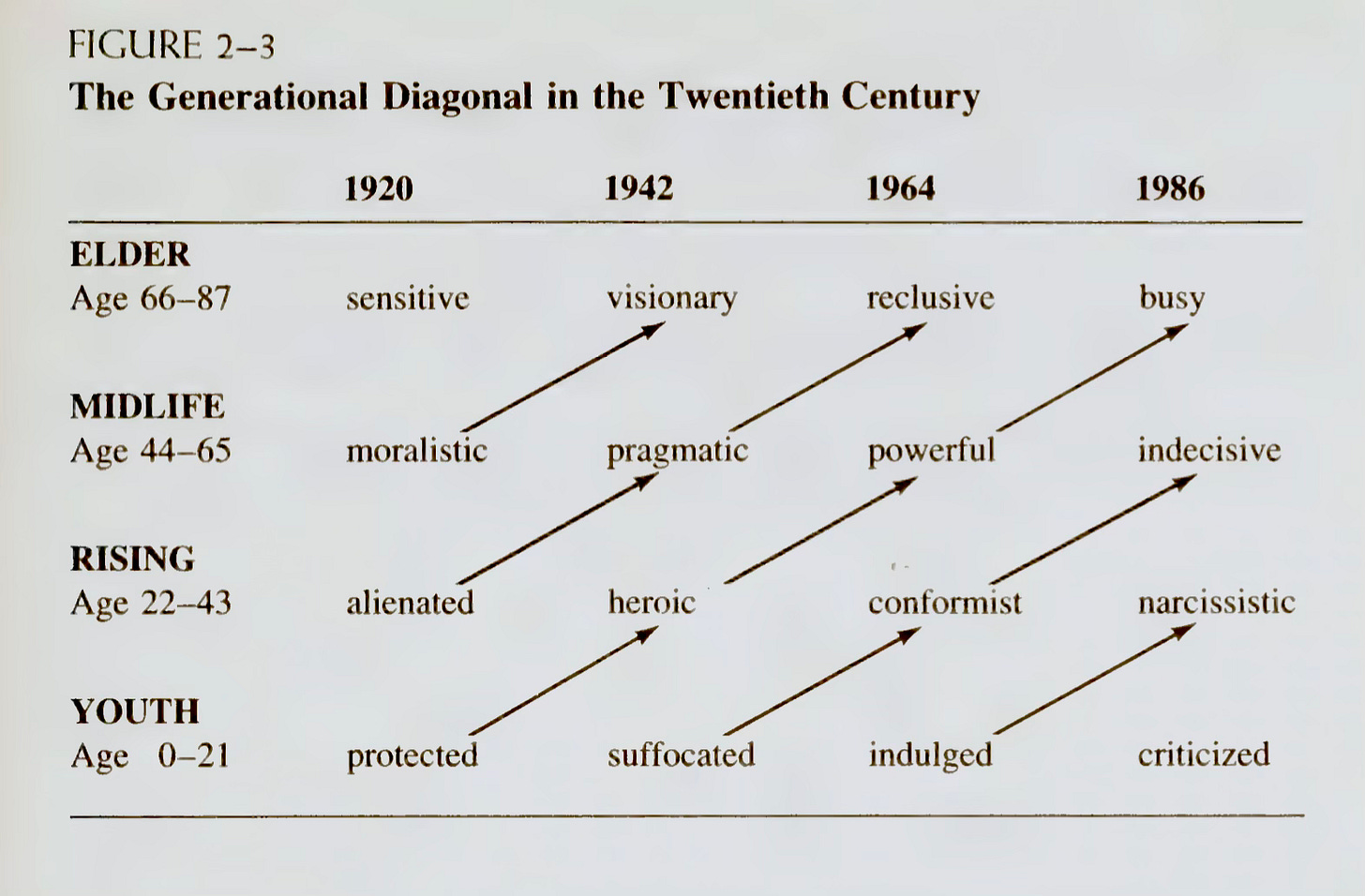

A fine book, but hardly the origin of a consulting empire. Strauss and Howe’s real theory is very different, and much stranger. Generations, they claim, have distinctive characters or temperaments, and those characters recur in predictable cycles about every 88 years. It works like this: each generation lasts approximately 22 years, corresponding to one life phase. Youth stretches from birth to age 21, rising adulthood from 22-43, midlife from 44-65, and “elderhood” from 66-87.2 At any given moment, all four groups will have their social roles; some will be dependents, others will be entering the workforce; some will be pulling the levers of power, others stepping back from it. They’ll also all have familial roles, as children, parents, and grandparents of one another.

Each group creates the environment for the others; when groups with certain characteristics came of age, their children will be shaped by their parenting styles and ideas. You can get a sense of the range of parenting styles, and personalities, in the chart above.

Dramatic historical events crystalize styles of behavior, which, in turn, have an impact on the next generation: the generation who fights in a war will behave differently than the generation who manages it from the home front. The cycle quickly becomes self-reinforcing. Every forty years, a political crisis tends to recur with the changing of generations; every eighty years, the cycle repeats, in an epochal historical moment that the authors refer to as “The Fourth Turning,” a phrase that strains hard for sinister charisma.

It’s a complete interpretation of American history, so long as you regard American history as a hermetically sealed sphere, shaped only by the imperatives of a homogenized population, fundamentally united in everything—class, race, sex—except age bracket.3

Any theory that adopts a minutely numerological approach to history tends to descend into the ridiculous. Inevitably, timelines get fudged and boundaries get blurred as its proponents, like hapless Ptolemaic astronomers, attempt to save the phenomena. Cyclical theories have a particularly poor track record in this respect: the crises they predict rarely come exactly on schedule.4

But it’s easy to see why proponents of generational history are drawn to the idea of larger cycles.5 After all, the convergence of the cyclical and linear is at the heart of generational theory. Generations are inevitably cyclical, because they track the movement from birth to death that all human beings experience, again and again and again throughout history. But when, in the twentieth century, generations began to be given names and treated as unique phenomena—The Lost Generation, Zoomers—they also became an index of linear, historical change.

The competing pull of the life cycle and historical change makes generations a fraught concept. In practice, it’s not easy tease out effects of youth and age from the social and historical phenomena that accompany them, much less to understand the exact nature of their entanglement.6 In general, social scientists don’t typically use generations, referring instead to cohorts.

But the convergence of the grand sweep of history and the minute scope of the life implicit in the concept of the generation, I’ve now come to think, is exactly why we need it. Generations are how literature seeks to interpret history—and how we all do in our own lives. Long before the modern generation emerged in the twentieth century, before the eighteenth century began to fit past and future into an endless arc of progress, social change took a human shape in the tensions between and possibilities opened by successive generations.

Strauss and Howe’s odd, prophetic schemes won’t help us here. But what’s the alternative? So far English-language scholars have made only limited use of generations: one of the historians in the American Historical Review conversation remarked that, despite using the term in the title of her monograph, she’d never really thought about it as a concept.7 Silly models of generational theory should spark more serious investigations rather than discouraging them.

But Is There a Theory of the Iliad?

I’m happy to report that there is, in fact, a theory of the Iliad. All aspiring master theories need a novel interpretation of the Bible or Greek literature. After all, to return to the earlier metaphor, it’s hardly a key to all mythologies if it can’t unlock even one solitary myth. It’s buried in the appendix, which is a bit disappointing: by all rights it should have been the opening sequence. Still, so far as such things go—and for me they go very far indeed—it’s pretty fun.

The idea is that there are four generations represented in Homer’s Iliad, each about 21 years apart from the last, and each representing four temperaments in keeping with the different social roles of each. In other words, the Iliad represents generational position as temperament, and it reveals how crisis events create temperamental differentiation, which is then presumed to be stable over time. Or, as Strauss and Howe put it,

Letting time pass after the war is over, we notice the continuing influence of the social moment. Twenty-two years after the social moment, when each generation has risen one phase-of-life notch, four distinctly different peer personalities still exist. Those who were elders during the war have passed on, but a new crop of youths (all born after the war) has arrived. Having no firsthand memory of the trauma, these youths develop a peer personality unlike that of any of the elder generations. Assume, for now, that nothing else happens thereafter.

The format is one I’d like to see more journals and magazines adopt: a new conversation every year between big names and up-and-comers, conducted over email over the course of months, then published. Then a panel is convened at the AHA meeting to continue the conversation and open it out into a general discussion. Easy to see how cultural journals, not just scholarly ones, could imitate this. (Perhaps it’s not miles away from what

is already doing with its salons.)This is a little unconventional: traditionally, generations were thought to last 30 or 33 years, the average time it took for groups to reproduce; contemporary generations, whose timing owes more to technology than biology, tend to last only 15. But it has its own logic.

In fairness, Strauss and Howe do try to take these things into account in their description of historical changes. But the structure of their analysis militates against ever taking them too seriously: other factors can accommodated as narrative, but not as theory.

I can’t help it, I like them anyway. If anyone wants to discuss cliometrics, let’s talk.

Strauss and Howe are hardly the first: Ibn Khaldun comes to mind, to name just one. Generations is a bit like someone putting the Muqaddimah into a blender with a bunch of old issues of Newsweek.

The recent discourse on Substack and elsewhere on the disappearance of the young author and the young celebrity, by

and , offered a good introduction to some of these ideas.At least in literary studies, the concept of generations plays a more important role in French, German, and Spanish theory than in English—perhaps its not a coincidence that the originary theorists of the generation (Mentré, Mannheim, Ortega) come from those three languages.

This is such a fascinating thing to open up. Influenced by old Penguin anthologies as much as anything I learnt about modern poetry as a series of "movements" (in the UK I guess that means: the Romantics, the Victorians, the Georgians, the Modernists, the Communists, the Movement). Demography is taken for granted, rarely explored. Of course each movement has to write its generation in its own image, so it's an artificial process to an extent, but not entirely...

They give critics something to hang on to, too. I sometimes think a key "problem" would-be critics face now is that those generations don't coalesce in the way they used to, so that whereas in the past you could convince yourself something was genuinely at stake when you waded into an argument, now you're so obviously dealing with fashion, broken conversations and half-measures not to mention the plausible deniability (I think you can still see generational patterns e.g. in British poetry, but the poets would deny it and there's little appetite for discussing it) that there's little point in staking out a position... which perhaps all relates back to Substack and networks... perhaps twas ever thus...

Fascinating discussion, thank you Julianne. You may not know this:

https://www.cdamm.org/articles/strauss-howe