An Open Elite?

Literature and Social Mobility in Perspective

Victor Dubreuil, “Barrels of Money,” c. 1897

Writers and Money

It’s not easy to make a living as a writer. As Elle Griffin, Erik Hoel, and others have discussed on SubStack recently, the mid-list author is an increasingly rare phenomenon: today, publishing follows a power-law distribution, where a few bestsellers generative massive sums, and virtually everything—and everyone—else makes next to nothing. For the vast majority, literary writing isn’t a source of income, but a time-consuming, unremunerative pursuit, open only to those with wealth and leisure. “To have money is becoming of more and more importance in a literary career,” a character in one novel remarks. As inequality rises across the board, the elite nature of literary authorship becomes a symptom and an emblem of a society where social mobility has stalled.

It’s not great. But. My aesthetic center of gravity is a period when knights and earls were laying the foundations of English poetics. Lord Byron, the literary celebrity of Romantic-era Europe, was a baron. These facts were not lost on contemporaries. The greatest novel about the difficulties of making a living as a writer, Balzac’s Lost Illusions, was written between 1837 and 1843. The quote in the paragraph above comes from George Gissing’s 1891 masterpiece, New Grub Street. There’s a long history to literary inequality and to literary complaints about it.

What makes it so unsettling now is that we, many of us, grew up with the feeling that inequality would recede with time, that the future would move inevitably, if not effortlessly, toward universal opportunity. But, as I discussed in a post on Walter Scheidel’s The Great Leveler, the reverse is closer to the truth: rising economic inequality is the rule, while egalitarian ages are the exception. Unsurprisingly, this means it’s very hard for individuals to move up the social scale. Gregory Clark argues that social mobility has been more or less uniform throughout English history, both before and after industrialization, with about a .82 correlation between the status of an individual and his (he’s looking at men) family. This is very high. It turns out that the Cold War era, which did so much to shape our sense of the arc of history, was a very unusual time.

To what extent, then, are we simply seeing the end of the post-war exception, a period when the world was destroyed and new societies had to be remade in its ashes? That wouldn’t make decreasing social and cultural mobility less important or less alarming. But the long-term perspective inevitably opens up a different set of questions and a different sense of future prospects. Besides, literary history is valuable in its own right: it’s the intellectual biography of humanity, a vital part of our shared life story. We don’t understand ourselves if we don’t understand this.

So how much social mobility was there within the whole canon of English literature? What were writers’ backgrounds? And how did they change over time, if, in fact, they changed at all?

It’s not an easy question to answer. Studies of social mobility usually begin no earlier than the nineteenth century, when modern censuses allow us to link records across generations. When it comes to literary history, scholarship is even slimmer. Again, there’s research on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including a very good study from 1850 to the present, which concludes that “access to financial resources within a family facilitates the uptake of an artistic occupation,” i.e., most artists come from money. But, so far as I can tell, only one scholar has tried to assess the class background of English literary writers from the beginning of the Gutenberg age on: Raymond Williams.

In “The Social History of English Writers,” Williams analyzed the backgrounds of 350 English writers born between 1470 and 1920. What emerges is a rough but fascinating sketch, which gives our impressionistic sense of literary history a firmer basis: the early Tudor period and Restoration as aristocratic eras (Surrey, Rochester), the Elizabethan period, by contrast, as drawing from both the gentry and mercantile classes (Sidney AND Shakespeare). Romanticism as unusually socially mixed (Byron—but also Blake), Victorian literature as dominated by authors from professional and middle class backgrounds (Trollope, Arnold). Williams clearly anticipated that other literary scholars would add to and refine his picture, but they haven’t done so. I find that puzzling: given all the things we know about authors, the vast repositories of research into literary biography, why isn’t our collective picture clearer?

Inevitably, Early Modernity

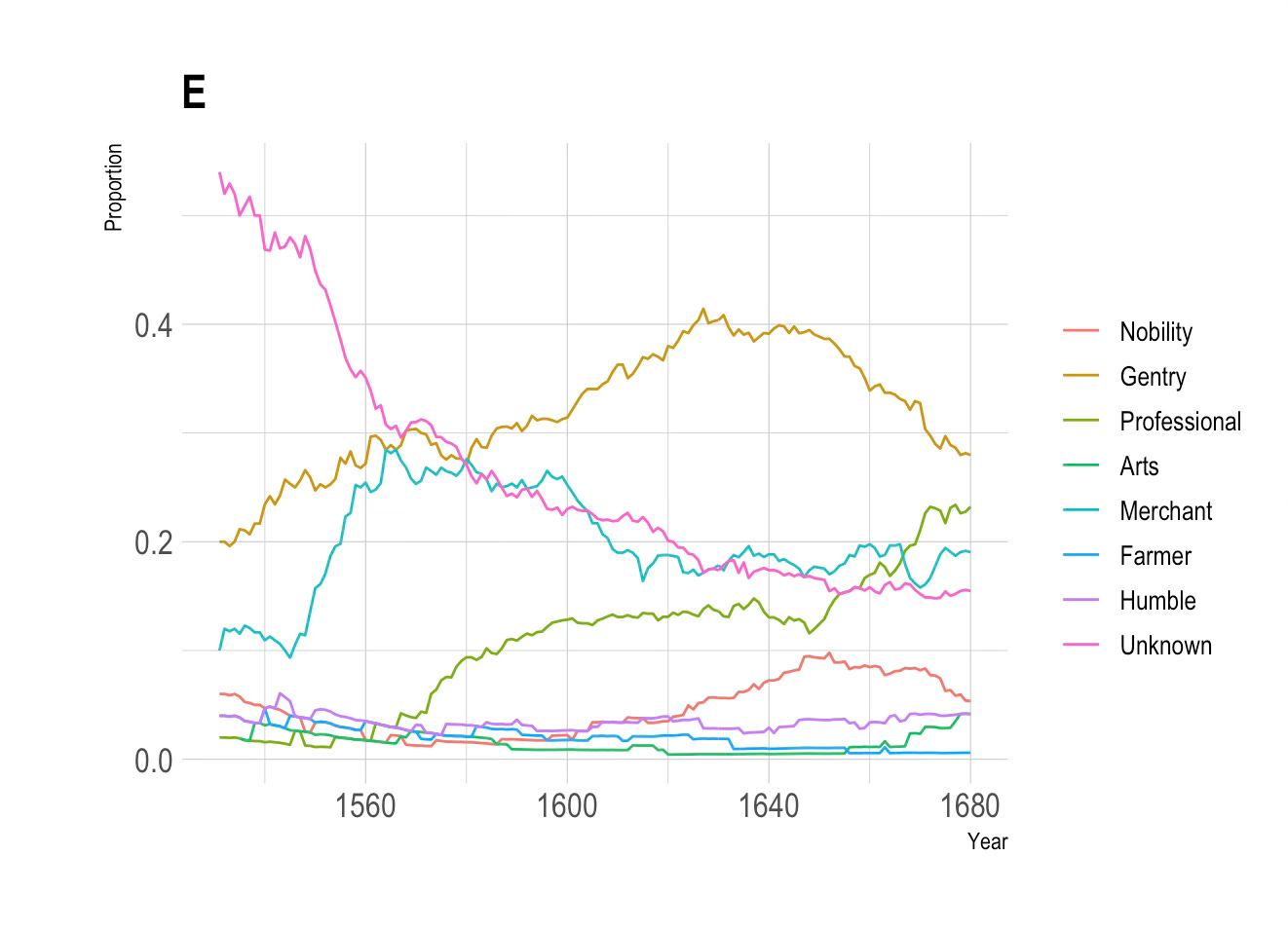

In the spirit of Williams, then, here’s a quick sketch of authorship, class, and social mobility for the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, based on my analysis of around 600 literary authors. Assembling this information meant making a lot of tough calls. Human lives don’t always accommodate themselves to well-defined categories, and the lives of authors and artists are messier than most. Where on the social hierarchy, precisely, do you put pirates? What about the many parasites and con artists, like Richard Vennar, nicknamed “England’s Joy” after his most famous scam (a story for another post, perhaps). Investigating them at a distance of half a millennium, with all the gaps that entails, doesn’t make things easier. Still, I’m reasonably confident that, despite many marginal cases and a few catch-all categories, the pattern holds.

The big picture: to begin, writers were only drawn from the upper and middle layers of society, never the bottom half or, more realistically, the bottom three-quarters. For this purpose, the rural, laboring population is simply not in the frame. Overall, social mobility was .84: just about the number Gregory Clark got, meaning that most writers were born and died in the same, broad class. But there were some important exceptions, and some noticeable variations in which social groups writers were drawn from across the period:

Writers’ background by year of birth, measured cumulatively in 50-year intervals. Graph by my excellent research assistant Pablo Bello.1

The Elizabethan period saw a surge of new writers who were the children of merchants and tradesmen, while in the early Stuart era and early Restoration, the gentry again wrote most of the period’s literature. Then, toward the end of the period, the share of the gentry and nobility fell, while children from professional families, and with parents working in the arts, rose. Or, to put it another way, we see a period when the literary field was more open toward the end of the sixteenth century, followed by a period of constriction and social closure for most of the seventeenth century, concluding, at the very end of the century, with another period of rising openness.

This is aligned with Williams’s findings, as well as with much of the scholarship on each of the eras in question. But I think putting it in such a stark form helps us not only to understand early modern literature, but also to glimpse some of the fundamental dynamics of English literary history. While most people outside the elite would never become authors, there were moments when the market for writers and educated professionals—the groups who wrote for a living in one form or another—expanded sharply, creating new openings for men and, later, women, from outside the gentry and nobility. In the Elizabethan era, the rise of the theater created a new literary profession, while the church and law both expanded: lawyers and clergymen wrote a lot of books. At the end of the seventeenth century, journalism exploded, pulling in writers such as Defoe and the young Addison, as well as innovative unknowns like John Dunton, the first to write a serialized newspaper column answering readers’ questions, The Athenian Mercury. Talk about a lasting literary genre! At the same time, the beginnings of the party system created new places for pens-for-hire, and new spoils for the faithful in the form of political sinecures.

As literary periods, both eras share deep similarities. Both are ages when new and lasting popular genres sprang into existence. They’re ages of drama and prose fiction, experimenting with, and gradually mastering, long-form storytelling, especially comedy. They’re also important periods for literary criticism: the Elizabethan period produced the first, soaring declarations of the majesty and power of English literature, later polished, made at once subtler and narrower, by Dryden and Addison. These are all characteristics of expanding literary fields: innovative forms written by new groups of authors; a fresh belief in the power and independence of the artist. As Theseus, one of English drama’s first literary critics, proclaims in A Midsummer Night’s Dream,

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.It would be hard to find a more forceful statement of confidence than that.

After the seventeenth century, the overarching story of literature was one of growth, for reasons both internal and external to literature itself. But that growth was never perfectly even: there were always fits and starts, periods of comparative tranquility, when the literary field was less open and writing became more baroque, and then periods of sudden acceleration, when people from lower social tiers, new regions, or different backgrounds suddenly surged into the literary field.

None of this implies a mechanistic approach to literary history, much less to individual literary masterpieces. There is no straight line that can be drawn from the birth of the theaters and growth of the professions to the searing poetry of King Lear or the dizzying irony of The Alchemist. But I think there is still something important, and even moving, that we can learn from thinking in these terms. Literature is inseparable from the lives of the men and women who make it. It’s not just the fluctuations of style, genre, content, or structure. The very idea of literature as something distinctive and intrinsically valuable is predicated on the idea of the author as a unique character in our shared social drama. This is a point I want to come back to in a later post on the history of English literary criticism, which is biographical and authorial from its origins on. Sidney’s Defense of Poetry is, in reality, a defense of the poet. To understand the social history of literature, we need to understand readers, markets, and media. But we also need to understand authors, the figures who connect the wide, shared world to the small, beautiful rooms of literary art.

A note on categories: “merchant” includes everyone from small tradesmen to the genuinely wealthy; “farmer” includes yeomen and farmers in the technical sense, but not husbandmen; “humble” indicates that we don’t know what a writer’s family did, exactly, but we do know they weren’t a member of the gentry. (It’s the word they typically use, but I should find a more contemporary phrase.) Many categories, including all those lower down the social scale, are absent: that’s because authors by-and-large did not come from them during this period.

An interesting study, and certainly a timely lens to think about writing as a profession—especially given the Cambrian explosion of writing on the internet, yet “writing for a living” becoming increasingly the domain of the relatively few, as so many recent conversations on Substack and elsewhere highlight.

I wonder, too, how these trends would fare compared against general numbers regarding literacy, for example, and literacy broken up by gender and class as well. It seems inevitable to me that writing would begin, at least, as an elite occupation simply because only the very elite were literate to begin with (elite and clergy, of course, who were often drawn from elites too). Folk of more humble classes (I also can’t think of a better term!) would rely instead on oral traditions such as tales and songs, which are much harder to track and trace, in their pre-written-down forms.

I’m also curious about what other factors would help contextualize the interesting graphic you’ve presented. Political movements, perhaps? I.e., is there a correlation between increased literacy or populist movements, for example, and the periods of relative openness for writers to enter the field? Or, if not political movements, then maybe broadly socio-economic or even technological opportunities?

Certainly a fertile field of research! I am looking forward to hearing more about your work on this, and the patterns that emerge :)

Really interesting and well researched. I'm in the middle of reading Great Expectations so of course I thought of the singular data point of Dickens.