Levellers

Mortality, Equality, and Literary History

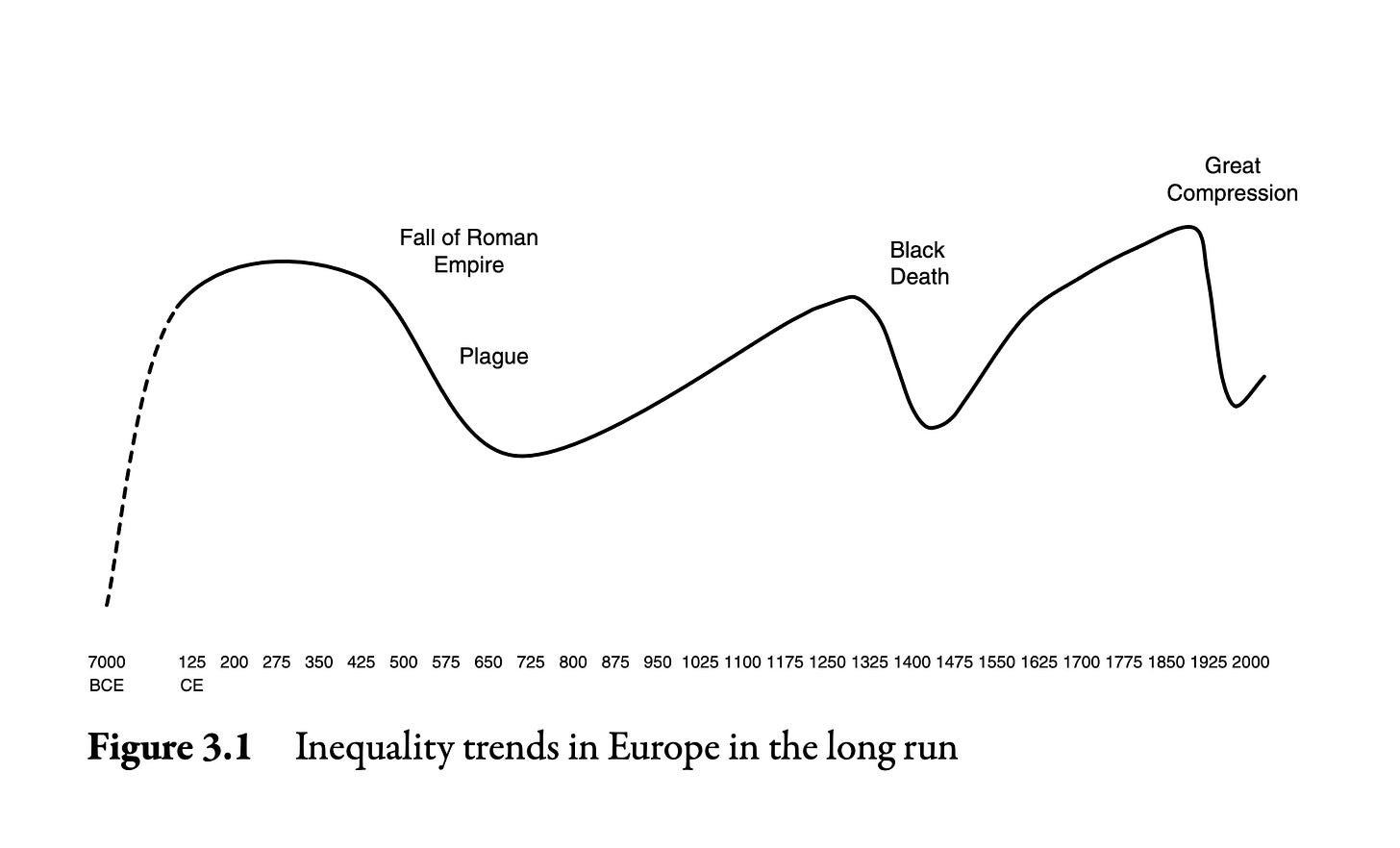

Image from Walter Scheidel, The Great Leveler, p. 87.

Following the financial crisis of 2008, economic inequality was added to the roster of pressing problems facing the world. Activists demanded solutions and politicians promised to address it. David Graeber’s Debt became a bestseller and Obama called inequality “the defining challenge of our time.” Meanwhile the gap between rich and poor continued to grow, with newly minted billionaires controlling an ever-larger share of global wealth. Today, Bernard Arnault, the current richest man in the world, possesses about as much wealth as Croatia. Reversing course seems impossible. But according to the Stanford classicist Walter Scheidel, there is one thing that we know, with certainty, can make society more equal: mass death.

I’ve been rereading Scheidel’s grim work of macrohistory, The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century (Princeton, 2018), as I work on a chapter on literature and social mobility in early modern England. It’s an intriguing book with a simple, provocative thesis at its core. The argument goes like this: over the millennia societies have tended to slide slowly toward increasing inequality. Some might think of economic modernity, with its amazing potential for growth and sophisticated division of labor, as an egalitarian force. But if anything, it’s the reverse. Economic development, in creating more wealth within society as a whole, makes greater inequality possible. This is because when groups operate at or near a subsistence level, there simply isn’t as much of a surplus for elites to appropriate. Everyone is, of necessity, a lot closer to being equally poor. As wealth grows, however, extreme disparities become possible. Urbanization, commercialization, and intensive growth boost inequality. Elites capture the majority of resources, and they hold onto them tightly. Only cataclysmic events, marked by a sharp death toll, are capable of loosening their grip.

There aren’t all that many such events: the death rate has to be very high indeed to transform society. Revolutions can work, but only if they’re carried to completion, with an unshakable will to remake the social and economic order. So the Russian Revolution qualifies, but not the French. Civil wars and state failures tend to reduce inequality, but they do so by making the rich poorer, not the poor richer. When a state crumbles, everyone loses; there’s wealth compression, but it just means that the whole population is nearer to the bottom. The best examples of events capable of truly shaking up the social order, by far, are pandemics and modern, mass-mobilization warfare, as exemplified by World War I and II. With their tremendous destruction of life and, in the case of war, capital, they create new economic opportunities, enriching and equalizing whatever proportion of humanity is lucky enough to survive them.

This, in a nutshell, is Scheidel’s picture of the course of world history. It’s an extremely distanced view, grounded in large-scale demography, and that comes (dare I admit it?) with some limitations. Transnational population shocks are, after all, few and far between, and it's a big theory to hang on a handful of incidents. Politics is, if not exactly omitted, certainly sidelined, and a lot of important events don’t show up, including some with far-reaching significance.

Take the English Revolution or, if you like, the English Civil War, an event Scheidel doesn’t mention, oddly enough. It’s true that the death toll doesn’t compare to plague or modern mass warfare: in England and Wales, perhaps 85,000 were killed in combat out of a population of around 5 million, or .17%. If you add war-related disease, the number goes up, but no year in the 1640s makes the top ten for years of excess mortality in England and Wales in the period (if you’re wondering, the top year is 1557-8, by a huge distance). Perhaps that’s part of the reason that the English Civil War didn’t result in a major, long-term redistribution of resources. And yet I can’t help but feel that it played a role in the history of inequality that goes beyond its immediate impact on England’s Gini index. Death may be the great leveler, in Homer’s phrase, but the English Civil War gave rise to real Levellers, whose vision of political equality was reflected in one modern revolution after another.

Still, as the grandest of narratives, Scheidel’s theory has a certain plausibility. Escalating inequality periodically reversed by mass disaster: it’s an unorthodox summary of the long arc of history, to be sure, but you could do worse. More importantly, for my purposes, it strikes me as an intriguing framework to bring to bear on literature and culture. Scheidel doesn’t touch on this dimension of history at all, but it’s easy to see how his ideas complement long traditions of scholarly research.

Take plagues. Boccaccio, Petrarch, Chaucer and Langland all wrote in the shadow of the Black Death, and they bear its imprint both implicitly and explicitly. Implicitly, because they were all part of the European movement toward vernacular literature rooted in commercial, urban environments with high social mobility—trends that accelerated in the aftermath of the plague. And explicitly, because the works of this period show a new preoccupation with the nature of social hierarchies and the mixing of social groups. In different ways, these are fundamental questions in The Canterbury Tales and Piers Plowman alike. Whatever the precise economic and demographic implications of the Black Death—and check out the JMEMS special issue “Population and Society in Medieval and Early Modern England” this summer for some new theories!—it’s impossible to envision either the socially adroit and slippery writings of Chaucer or Langland’s savage meditations on corruption and labor without the leveling effects of the plague.

If we go back more than a millennium, to the Antonine Plague of 165-180, we find a similar reckoning with the problem of social equality. This pandemic, which may have been smallpox or measles, killed between a quarter and a third of the Roman population. Again, we can see a cultural and intellectual response. In this case, though, it took the form of Christian teachings: the period following the Antonine Plague is when Christianity achieved critical mass, with more than a million converts by the middle of the third century. Some scholars, including William McNeill in his classic Plagues and Peoples, and Rodney Stark in The Rise of Christianity, have connected the period’s pandemics to religious conversion. But neither do so by way of the question of equality, which early Christianity expressed in the most resonant of forms. Who is the rich man who is saved? Clement of Alexandria asked in the immediate aftermath of the Antonine Plague.

What these examples suggest, to me, is that looking at plagues, wars, and other forms of mass death as potential equalizers could reveal new points of connection and comparison between eras and regions. It might help us draw lines that lead from early Christianity to Langland to Milton and beyond. I’m curious if others reading this can think of other incidents, macro or micro, where a similar analysis might apply.