The group is present in consciousness even when the individual is alone: for individuals who are the creators of historically significant ideas, it is this intellectual community which is paramount precisely when he or she is alone. A human mind, a train of thinking in a particular body, is constituted by one’s personal history in a chain of social encounters.

Randall Collins

Sociology and / or Aesthetics

It’s hard to be a sociologically inclined aesthete. Today, sociology and aesthetics often appear in opposition, enemies facing off on the intellectual battlefield. On the one side, individualism, preferably on the heroic scale, and a sharply graded sense of artistic quality; on the other, collectivist accounts of meaning and the reduction of art to mere ambient culture. On the one side, great men and great books, rising like Mount Parnassus above the level plain of humanity; on the other, the mundane, inglorious forces of history that encompass us all and in which we all participate. The muses versus the market; idealism versus materialism; right versus left.

In reality, of course, most of us still occupy some kind of middle ground. We’re dazzled by works of genius and interested in the conditions in which they were made. The closer we are to novels or plays or poems, the more easily we can see both at once: ask a novelist about his or her fellow writers, and you’re unlikely to remain in the pristine world of ideas for very long.

Usually, our movement between questions of aesthetics and questions of social or biographical history is pragmatic, driven by the imperatives of a particular mode of discussion or our own curiosities. “I don’t want to just read about a line from ‘The Bridge,’” a friend of mine, a poet, remarked the other day. “I want to know what Hart Crane was having for lunch the day he wrote it.”

But it’s also possible take a more theoretical approach to the intersection literary quality and social history.1 After all, there’s sociology of elites2 as well as sociology of the masses; sociology of institutions and networks as well as sociology of populations and classes. By all rights, it should be possible to write a sociology of intellectual achievement.

The Sociology of Philosophies

That’s precisely what Randall Collins set out to do in his magnum opus (emphasis on magnum) The Sociology of Philosophies, first published in 1998. Collins is a former president of the American Sociological Association, but he’s also a brilliantly idiosyncratic scholar. His books touch on everything from violence to ritual interactions to credentialization, moving between topics and methods with the elegant touch of a latter-day Durkheim. To write his book on violence, he apparently watched tens of thousands of hours of surveillance footage of brawls; he also seems to have reread The Iliad pretty carefully. (It’s an interesting study.) Insights, and page counts, evidently come easily to him.

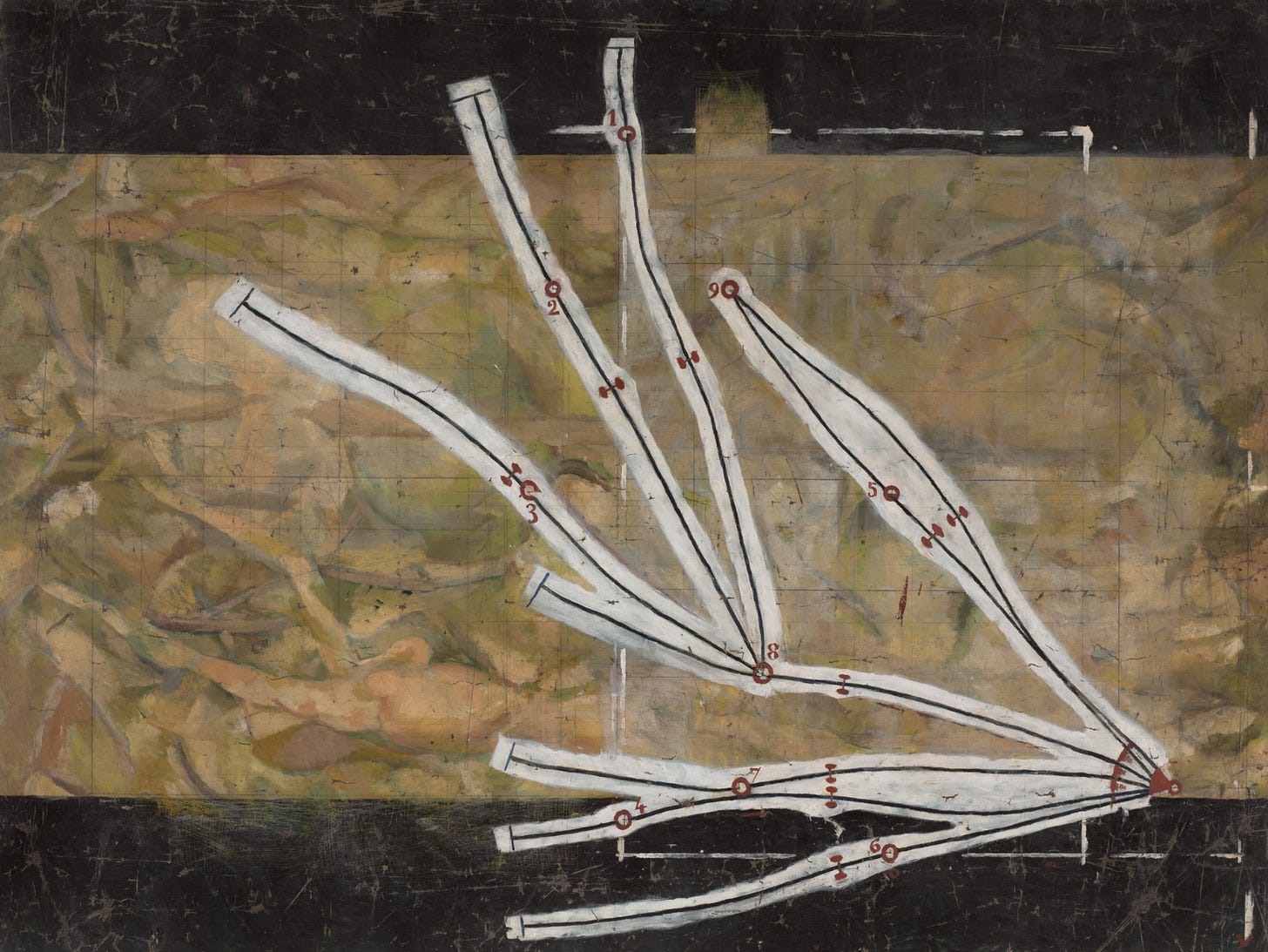

Even by his own standards, though, The Sociology of Philosophies is an odd, ambitious book. It’s a theory of intellectual life in the abstract, but it’s also a global history of philosophy, with chapters on the major events in European, Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, and Indian philosophy. It’s full of massive, unwieldy diagrams and detailed tables. Abstract, lapidary formulations of the nature of thought alternate with detailed accounts of internal rivalries among medieval Franciscans or Warring States era Confucians. As this precis should imply, it’s also very long: about 1,000 pages.

Here’s how the theory works.

According to Collins, intellectual life, at its core, is conversation. No matter how solitary we think we are when we arrive at our ideas in the quiet of a monastic cell or the privacy of a study, we inevitably reproduce, reply, and react to the words of others. Language is social; so are its mental echoes, thought. In the case of philosophy, it’s not just any kind of conversation: it’s argument. Conflict, not agreement, propels ideas forward.

The competitive character of philosophy doesn’t make it anti-social, though. Quite the opposite! Just as a soccer match can’t be reconstructed without all of the players’ moves on each side, rivals’ ideas are made possible by each other’s. Hence the Socratic dialogues, which make obvious the structure of real, highly charged, interpersonal debate that informs all philosophy, have such a totemic quality. Someone—the abysmally ignorant rhapsode Ion; the arrogant rhetorician Gorgias; the dangerous political realist Thrasymachus—is always offered up as provocation to philosophical progress.

As with soccer matches, though there may be tiny scrimmages everywhere, the number of important events at a given moment, the arguments that attract strong adherents and opponents, is finite. For one thing, it’s difficult to develop genuinely new lines of thought. More fundamentally, attention is limited. In any generation, within any intellectual field or subfield, interest invariably coalesces around a small number of positions or tendencies. In fact, according to Collins, that number is between 3 and 6. (One of the charms of the book is in such moments of daring, and possibly unjustifiable, precision.) “Not warring individuals,” Collins writes, “but a small number of warring camps is the pattern of intellectual history.”

The philosophers at the center of these networks of rivals and allies are the important ones: the intellectual luminaries who configure the space of debate in their own moment and for the ages to come. They’re connected to the other ideas and other figures worth knowing via their predecessors, whose arguments they use and react to; their contemporaries, with whom they debate or ally; and their successors, who take their thought in new directions. In fact, that web of intellectual connections is what genius is, sociologically speaking. “Reputation is not really distinct from creativity,” Collins remarks. “What we consider intellectual greatness is having produced ideas which affect later generations, who either repeat them, develop them further, or react against them.”

This, then, is the theory at its core: intellectual achievement as network centrality.

Today, thanks to digitization—and our tendency to project the nomenclature of our perpetually online lives into the past—Collins’s insight might have the ring of cliche. Network analysis has become something of a micro-industry, including innumerable reconstructions of historical networks, from sixteenth century political letter writers, to the world of Renaissance print, to the complete contents of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, to name just a few. There are also growing numbers of studies of texts that see them as nodes within networks, linked by structures of reference and allusion.

In 1998, when The Sociology of Philosophies appeared, network analysis was still a relatively new field, and Collins’s account was unique in both its historical emphasis and its sheer scope. And in some important ways, it remains unique.

What distinguishes it from any other network analysis I’ve read is how seamlessly Collins brings together real, embodied social networks and the structure of debates conducted mostly in books. Even in his account, they’re not identical: peripheral figures can and do make central contributions to thought. But they’re brought far closer, made far more relevant to one another, than in any other study I’ve read. The human social world, where real conversations happen, blends seamlessly into the abstract world of philosophical argument without doing injustice to the complexity, abstraction, and autonomy of the life of the mind. It’s a sociology of intellectual life that doesn’t feel reductive.

The reason real relationships between people converge with philosophical achievements in books and articles is that debate, even on apparently perennial questions like the metaphysics of ideas or the reliability of the senses, is fast-moving. The field shifts constantly as new participants and perspectives enter the landscape. Talking to people helps you navigate it in a way that reading alone never can. So does being part of a concrete, social world, since institutional shifts frequently create new intellectual openings.

To take one example: the rise of Christianity could hardly have had a more profound impact on the topics of open to philosophical debate; a bishop, like Augustine, was in the thick of this transformation, and was therefore poised to grapple with its implications long before most of his contemporaries.

Here’s another. Over a millennium later, the beginning of the separation of the natural sciences from philosophy created a different set of possibilities. John Locke, who was a member of the Royal Society alongside Boyle and Hooke, was far better positioned to revolutionize philosophical empiricism in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (the word “essay” in the title is the giveaway, as I’ve noted elsewhere) than contemporaries in other countries.

Literary Networks

Does Collins’s massive intellectual history give us a key to the sociology of aesthetics, of literature as well as philosophy? Yes—up to a point. A few elements of his analysis are obviously useful: intellectual life as conversation, the constant, dynamic partitioning and restructuring of the space of ideas, the reciprocity between institutional change and intellectual life. At the moment, I’m in the early stages of thinking through a project on literary generations, in which I want to reflect precisely on the relationship between personal connections and literary change. I can see how a lot of Collins’s ideas will come into play.

But the way the sociology of philosophy diverges from the sociology of literature is also interesting. Networks are so powerful a tool for philosophical analysis because the field’s orientation is internal: it’s ultimately philosophers, not lay readers, who make or break philosophical reputations.3 (Kuhn made the same point about science in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; scientists’ autonomous network, in his view, was the enabling condition of progress.)

That isn’t true of literature, which has two faces, inward and outward. At least up to a point, lay readers, and not just other writers, matter to literary reception and canonicity.

The exact relationship between the two depends on the type of literature in question. In some cases, lay readership is everything. The opinions of other writers may matter to the author of commercial fiction in a personal sense, but they’re trivial in comparison with the public reception of the work, and they don’t shape its structure. The audience is ordinary people, not initiates.

Conversely, in certain kinds of experimental or avant-garde literary writing, almost all the immediate readers will be other writers or intellectuals (including aspiring writers and intellectuals, e.g., students: potentially a sizable audience). As Collins observes, there’s “a division between writers oriented toward the mass market and an inwardly oriented elite of writers pursuing their own standards of technical perfection.”

When literature is responsive toward its own networks, it tends to resemble, or even to become, philosophy. It’s argumentative, highly intertextual, and typically engaged with abstract ideas. Collins himself discusses a few cases of convergence, including the French Enlightenment (Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot) and Existentialism (Sartre, Beauvoir, Camus). But if we’re willing to cast our nets a bit wider, we can find similar tendencies among Renaissance humanists, metaphysical poets (the name, again, is the giveaway), modernists, and so on and on.4

I think there’s also something of the kind happening on Substack. There may not be another Voltaire or Diderot on here just yet.5 But I think we are seeing genuinely new modes of writing emerge among poets and fiction writers who are composing their posts largely for networks of others on the platform. It’s a model where there are few, or no, passive and silent lay audiences. Instead, the structure of the network presses fiction to become conversational, blurring the line between author and narrator, reader and interlocutor. It’s also frequently argumentative, at the edge of opinion and fiction, literature and theory (lowercase t). Perhaps that’s why the most exciting literary fiction I’ve read on here, like that of

, , or whatever it is is doing (I couldn’t possibly begin to characterize it, but I love it) tends toward the metafictional and the polemical.Without recourse, I should add, to Bourdieu!

As

explains in his account of Shamus Rahman Khan’s work here, and in his excellent interview with him.When philosophers attract enough lay readers, like Plato or Nietzsche or Kierkegaard, we often start to think of them as literature as well as philosophy. Philosophers can attempt to appeal to lay audiences, as well as to each other. But, Collins remarks, “the defensive syncretism in which intellectuals ally themselves predominantly with lay audiences has a strongly retrogressive effect on abstraction.” Ouch!

There’s an argument to be made that this is true of most poets.

We definitely aren’t in an era when princes and literary Substackers mingle in a modern-day Sans Souci, and, delusions of grandeur aside, I’m not sure we want to be. We all know how that story ends!

This book sounds great, bonkers in a fascinating way, and the post does a great job presenting it, threading the needle of debates people have been having here on Substack. I guess that I have some predictable reservations about Collins as you present him, which I think you have as well. His theories about how networks operate aren’t social science in the sense of offering a cause-and-effect model, and they abstract from how members of a given network understand what they themselves are up to. (Probably not *that* much, if Collins could have a drink with Pico della Mirandola, Pico would maybe admit that Collins had understood a lot about the Renaissance).

I seem incapable of writing short, non-pompous comments on this website, so here’s a too-long one: “Philosophy” in the western and Islamic worlds is a user’s category, going all the way back to Hericlitus. So a sociology of philosophy from the Eleatics to Patricia Churchland is the study of a 2,500 year old continuous living tradition that’s always been more or less self-conscious. “Literature” I think did not become a user’s category until the early 19th century? I’ve always been told the modern meaning of that word comes from Mme. de Stäel, but now that I type this it sounds wrong. You’d know better than me: of course the idea of literature has a thousand precursors. Anyway, Plato distinguished philosophy from poetry, the telling of beautiful lies about the gods. Whatever he meant by expelling the poets from the city, Plato like Parmenides produced great literature by any standard. The effort to make philosophy ugly has as often as not failed when the philosophy is good. Even in dry-as-dust analytical philosophy the greatest name is Wittgenstein, an extraordinary modernist writer. The other aspect of literature vs. philosophy you bring up is harder to quibble about: philosophical writing is often written for a smaller, self-consciously elite audience. But it doesn’t apply to the 18th century outside of Germany, or to the Discourse on Method. (I know you aren’t trying to draw a hard-and-fast distinction, really the opposite.)

Where might literature and the sociology of literature fit into the quarrel between philosophy and poetry? This is certainly my professional deformation speaking, but I’d date its emergence to A. W. Schlegel and Goethe, synthesizing ideas that had emerged in the 18th debates that gave birth to aesthetics. For them, works of literature (Schlegel calls all art “poetry”) are in part the products of different cultural milieux, of a Volksgeist or a national esprit in Montesquieu’s sense, determined at a first approximation by the nexus of language, form of government, mode of subsistence and religion. Schlegel draws a distinction between nature- and art- poetry, and if we’re charitable readers the distinction is still interesting. “Nature” poetry expresses of a culture’s mythological worldview, with the artist aspiring to anonymity. In “art” poetry the artist self-consciously transforms inherited genres and is appreciated for doing so. The emergence of this poetry results in a certain secularization of art, and the phenomena of recognizable generations and network effects. (These aren’t Schelgel’s terms, but they are what he writes about. What was romantic Symphilosophie if not networked philosophy that gloried in not distinguishing between philosophy and literature?). The secularization that “art poetry” brings about is incomplete because, beyond differences of climate and language, the differences between national literatures are connected to different worldviews, ideas about the cosmic or sacred. (This is true for Shakespeare vs. Sophocles vs. Calderon but even truer when it comes to the Bhagavad Gita, which Schlegel translated). The task of Kunstlehre or Literaturwissenschaft is to complete the secularization initiated by art-poetry through a process of comparison that takes seriously the milieu from which poetry emerges, in order to help make the self-knowledge literature gives us truly universal. (What I’m calling non-reductionist “secularization” Schlegel sometimes called a new or universal mythology, and of course he eventually became a cranky conservative, to the disappointment of Goethe and Hegel. But Schlegel’s inspiration in the 1801 Kunstlehre was Goethe, and the version of this ideal that comes from Goethe I at least find digestible.)

The ways of thinking about art that Schlegel opposed are still with us today. On the one hand there was the Platonic tradition of Leibniz, Malebranche, Shaftesbury (and their 18th century handbook-writing disciples). For writers in this tradition the content of art is Beauty which reflects eternal Reason, and the “sociological” details of the culture or networks of influence from which it emerged are of limited interest. On the other hand there was the materialism of the Enlightenment (La Mettrie etc.), which tries to explain the pleasure we take in different kinds of art in terms of the disposition of our “machine,” something which does not vary across cultures. This way of thinking secularizes you into a perspective where art is merely decorative. This is the case with Bourdieu, but also say Daron Acemoglu, who is supposed to be the rare economist who takes “culture” seriously. Contemporary social science presupposes and gives succor to a very reductive way of looking at life that is unable to find art interesting. The experience of great art can disrupt this perspective, but this experience tempts art lovers to an untenable platonism. I see the value of your Substack contributions as showing the writers and critics here that, firstly, like your friend who wanted to know what Hart Crane had for lunch, they are already interested in sociology whether they know it or not. Secondly, that actual academic sociology speaks to their deepest interests, even if the academic sociologists sometimes need a helping hand from you. It harkens back to the old romanticism in a way the new romanticism should appreciate.

Great piece Julianne! Btw I can’t think of a better model for how academics can communicate with a wider public than what you’re doing. You’re taking a very dense but very interesting text - the sort of thing that was, like, hidden behind academic publishing catalogs - and making it accessible to an engaged lay audience. It’s striking that not that many academics do what you’re doing (although obviously more now), and writing like this really helps to unlock a lot of knowledge.