At 4:30pm this past Thursday, I sat in a windowless room in the Boston Marriott, listening to a group of scholars discuss Francis Bacon’s utopia, New Atlantis. The conversation, conducted with all the erudition and wit its subject demanded, was a celebration of a new edition of Bacon’s philosophical fable, edited by David Colclough and soon to be released as the latest volume of the Oxford Francis Bacon.1

Meanwhile, in another room a few hours south on the Amtrak, Columbia University officials must have been putting the finishing touches on their capitulation to the demands of the Trump administration, which they announced the following day. Among other actions, they agreed to take the Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies department out of the hands of its faculty and place it under the oversight of the administration, in a profound violation of academic freedom. The Trump administration used the withdrawal of $400 million in National Institutes of Health funding to bring Columbia to heel, which to all appearances was almost effortless. It’s hard to imagine many other university administrations putting up a stronger resistance. With such an instrument at the administration’s disposal, and little public support or even—as yet—faculty will for a collective defense of the universities, the incidents at Columbia are in all probability a sign of things to come.

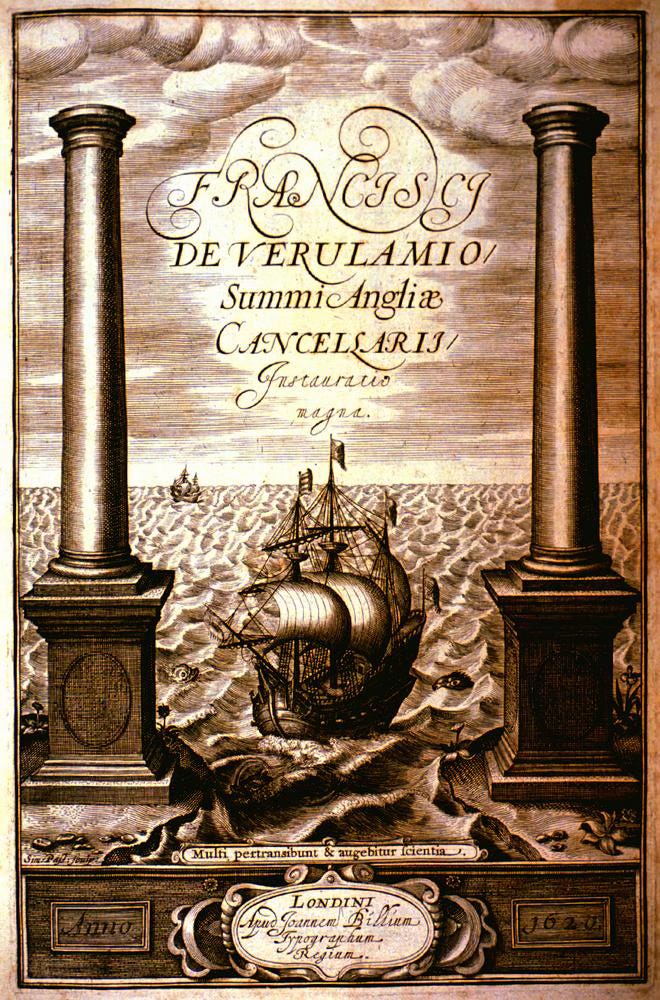

I couldn’t help but observe the proximity of the two events, and not only because the New Atlantis roundtable was led by a former chair of Columbia’s English department, the brilliant biographer and literary historian Alan Stewart. The real connection was conceptual. Bacon’s most powerful contribution to the history of knowledge was the model of the collaborative, technologically driven, massively expensive scientific research institute that is now the heart of the modern university, and the New Atlantis was the work in which he imagined it most vividly. Almost exactly four centuries after he wrote it, we’re still seeing the implications of the idea unfold around us.

In Bensalem

The story of the New Atlantis, such as it is, is simple. A merchant ship, sailing from Peru to China (no doubt stuffed from bow to stern with New World silver), is blown off course. Lost in uncharted waters in the South Seas, the sailors exhaust their food and water. They’re preparing themselves for death when they catch sight of an unknown coast, which proves to be an island called Bensalem. It’s a land of extraordinary prosperity, with sensible laws, useful institutions, and contented citizens.

Bacon, like the utopian writers before and after him, can’t resist describing a few of these; the utopia, after all, is a technocratic genre that revels in bureaucratic detail. There are public guest houses to quarantine visitors—more luxurious versions of a contemporary Venetian institution. There’s the Feast of the Family, a state-funded celebration of any man who has thirty living descendants above three years old (his female counterpart, whom one might think deserved a little celebration of her own, remains hidden, watching from an alcove). Best of all, in contrast to Thomas More’s austere utopian uniforms, there’s a riot of gorgeous clothing: “mantles of sea-water green satin,” a bevy of young men in “white satin loose coats to the mid leg,” “shoes of peach-coloured velvet,” bejeweled gloves, and parti-colored plumed hats.

The institution at the center of the story, the one that makes everything else possible, comes into focus about halfway through, when Bacon introduces Salomon’s House, also known as the College of the Six Days Works, Bensalem’s research center. The rest of the slim volume is a description of the work of the secretive scientists, their magnificent discoveries, and their opulent facilities.

The researchers have, for instance, towers half a mile high—about the height of the Burj Khalifa—and caves three miles deep, exceeding even the Mponeng Gold Mine in South Africa. They possess massive halls in which they create artificial meteors and ice storms. Zoos and parks hold every species of animal, not only for observation, but also for medical experimentation, “that thereby we may take light what may be wrought on the body of man.” Centers for optics include devices for projecting light and color, telescopes, microscopes, while in other buildings, every kind of sound can be heard or made. There are flying machines, speedy ships and submarines, and tragically, inevitably, “instruments of war” and “new mixtures and compositions of gun-powder, wild-fires burning in water, and unquenchable.”

It's extravagant beyond the wildest dreams of Renaissance avarice, in some cases even surpassing our own technological fantasies. But it's clearly worth every penny, for the work of Salomon’s House is what makes Bensalem’s prosperity, abundance, and perfect health possible. All those gorgeous velvet and satin clothes, the state-funded hospitals and delicious feasts, would be unthinkable without it.

The research institution, and the riches it enables, is what sets Bacon’s utopia apart from all previous ones, and above all from Utopia itself. While More imagined changing the way the fruits of human labor are distributed, Bacon dreamed of transforming the size of the harvest. Salomon’s House’s project, as its representative describes it to the travelers, is nothing less than “the knowledge of causes, and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of human empire, to the effecting of all things possible.”

A modest goal! But it was Bacon’s own.

Knowledge and Power

The New Atlantis was one of Bacon’s last works, left unfinished at his death in 1626 and published posthumously. But it had been a long time in the making. Just three years older than Shakespeare and Marlowe, Bacon was a member of the brilliant Elizabethan generation, unlimited in ambition and ruthless in pursuit of its goals. Unlike Shakespeare and Marlowe, he was born into privilege as the son of the Lord Keeper of England. Still, success did not come immediately. For decades, he struggled to climb the ladder of state, succeeding only in middle age, when he at last became Lord Chancellor. All the while, he observed his world keenly—keeping an eye on the overlapping spheres of the new learning, New World exploration and imperialism, and the burgeoning markets that were changing the very structure of society.

When Bacon turned his agile mind to the problem of understanding nature, he brought the whole of his experience and observations to bear on the topic. The gossipy John Aubrey tells us that William Harvey, the greatest medical mind of the age, complained that Bacon wrote philosophy “like a Lord Chancellor”—viewing the field from 10,000 feet in order to direct the work of others, rather than with careful, close-to-the-ground experimentation of his own. But that was precisely what made his scientific program so compelling.

Bacon had absorbed the intellectual lessons of his capitalist age and he explained them with easy authority. He demonstrated, for anyone who cared to listen, that the investigation of nature would not be abstract, speculative, and theoretical. It would no longer be pristinely isolated from the daily life and labor of society. On the contrary! It would be practical and, above all, profitable. Working collaboratively, philosophers could create a unified field of knowledge, capable of infinite expansion, and oriented toward the concrete, material improvement of human life. Bacon had other ideas, too: a superabundance of them. But this was the vision that animated his work from at least The Advancement of Learning (1605) on. Or, as Adorno and Horkheimer wrote,

Knowledge, which is power, knows no limits, either in its enslavement of creation or in its deference to worldly masters. Just as it serves all the purposes of the bourgeois economy both in factories and on the battlefield, it is at the disposal of entrepreneurs regardless of their origins. Kings control technology no more directly than do merchants: it is as democratic as the economic system with which it evolved. Technology is the essence of knowledge. It aims to produce neither concepts nor images, nor the joy of understanding, but method, exploitation of the labor of others, capital.

Written in the long and ongoing wake of European Colonialism, in the more immediate aftermath of the Second World War, and with the prospect of nuclear annihilation looming, it’s a dark interpretation of the Baconian program, but not a wholly inaccurate one.2 Others would invert its values, while leaving its central claim untouched.

The Idea of the University

The New Atlantis added one last piece to the Baconian puzzle in the form of Salomon’s House, the College of the Six Days Works. Bacon had alluded to the possibility of a scientific foundation before; now, for the first time, it was the centerpiece of the whole vision. In earlier years, he had hoped to see such an institution founded, under the patronage of King James, whom he addressed as a new Solomon; an echo of his flattery survives in the name of “Salomon’s House.” James, however, had little interest in the enterprise; in any case, by the time the New Atlantis appeared in print, he was dead. It was not until the reign of his grandson, Charles II, that the idea would take its first, tentative steps toward realization in the Royal Society.

From the start, the Royal Society was modest in scale compared to Bacon’s vision. But it shared his ideal of a well-funded experimental philosophy patronized by the prince and capable of making a practically infinite return on investment.3 “It cannot be imagin’d,” its historian and evangelist Thomas Sprat wrote in 1667, “that the Nation will withdraw its assistance from the Royal Society alone; which does not intend to stop at some particular benefit, but goes to the root of all noble Inventions, and proposes an infallible course to make England the glory of the Western world.”

The Royal Society was not a university, though Gresham College, where its members hosted early scientific lectures, at times resembled one. Nor, Sprat explained carefully, did its members seek to destroy the universities, with their theological and humanistic modes of learning. “I hope I have said enough,” he wrote rather ominously, “ to manifest the innocence of this Design in respect of all the present Schools of Learning; and especially our own Universities.”

Nevertheless, in the twentieth century, the fate of the universities became intertwined with the massively expensive, and also immensely valuable, scientific research institutes that did—and do—so much to transform human life. For the humanities, it proved to be a blessing and, more subtly, a curse. Humanistic study was the recipient of previously unimaginable largesse, reaching different groups of students, drawing in waves of new scholars, and taking up novel subjects. Yet it was also comprehensively remade, and as we all know, not always for the better. Today it struggles to retain even a peripheral place within the scientifically oriented and market-driven universities, adding its own pathologies in the process.

Now, it seems to me, we’re seeing yet another transformation of the universities. It’s symbolically fitting that it should begin at Columbia. The discovery—and the conquest—of the New World was always Bacon’s emblem of scientific learning. In the hall dedicated to honoring great inventors in Bensalem, the first statue is that of Columbus. Is it still possible for the incredible riches, material and intellectual, created by technologically driven research to be made compatible with free intellectual inquiry, cultural flourishing, and deep humanistic scholarship? Of course! But it would require a genuine will and a new, democratic movement, extending across the boundaries of the universities to the public and back, and working in both directions.

If not, I guess there’s always Substack.

They were Rhodri Lewis, Kathryn Murphy, Mickael Popelard, and Angus Vine. I can thoroughly recommend all of their work, except Mickael Popelard’s, which I don’t know; he is, however, apparently the French translator not only of Bacon, but of Sherlock Holmes.

It is, of course, inaccurate to suggest that Bacon, or the Baconians, took no joy in knowledge. Nothing course be further from the truth! I defy anyone to read Novum Organum without delight. And the Hartlibians’ enthusiasm is positively contagious. Yet the idea that such research would be useful for everyone, even those who took no pleasure in it themselves, was at the heart of their claim.

I describe the association between experimental philosophy and a new, materially useful form of knowledge that developed in Hartlibian circles in the 1640s and 50s in my article in The Cambridge Companion to the Essay, “The Essay and Experimental Science.”

Sorry to be the one from another field who strays into the conference and asks an off-topic question: but I couldn't tell from your post whether people in that session (or elsewhere in the conference) drew the kinds of connections you're making to contemporary universities. You're circumspect on Adorno's implicit verdict—is that just your own perspective? If it's not too general a question, I'd like to know if there's a literature on ways of thinking about Bacon's book in relation to the present moment, or the post-Humboldtian university in general.

Setting aside my thoughts about the panels themselves, my main reaction to the conference (my first time at RSA) was to wonder if I didn't finally understand that famous Talleyrand quote about life before the French Revolution. The older attendees (say, over sixty) seemed like bewildered aristocrats, not facing guillotine or exile but conscious of the wrecking ball that has been/is still being taken their world, almost unimaginably rich and delightful in the intellectual sense, and actually pretty decently comfortable in the wordly sense, too.

Meanwhile younger ones are not bewildered, they never had a terrestrial paradise. For the most part they are harried.